Portraits-encounters is a series of articles in the Canadian newspaper “Russian Montreal” about Chapiro’s encounters with the most famous subjects of his portraits (Sakharov, Tamm, Lifshitz, Leontovich, Plisetskaya, Rodnina, and many others). Kindly provided by Irina Lapina and the newspaper’s editor Lev Chif.

Original version in Russian is here.

Translation by Boris Rusakov. Proof by Mike Schecter.

From translator:

Changes made by translator are marked with the asterisk (*). They include: corrections of factual errors, adding dates of deaths for those who died since original version was published, removal of patronymics in order to make reading easier to English-speakers. Also, there are some explanations and comments added, without which I believe the non-Russian speaker could be confused.

Issue 12(87)

Mikhail Chapiro. The name of this artist is very well known to art lovers. His paintings done in the soft lyric manner do not leave anyone untouched. Mikhail considers the 70s and 80s as the most amazing period of his career. Then, in Moscow, he has made a series of portraits of famous scientists-physicists among which there were six Nobel Prize laureates. He has also made portraits of Great Russian ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, of famous Russian figure ice skater Irina Rodnina and of the star hockey player Alexander Yakushev. So, we decided to name our interview accordingly

“Portraits-encounters“

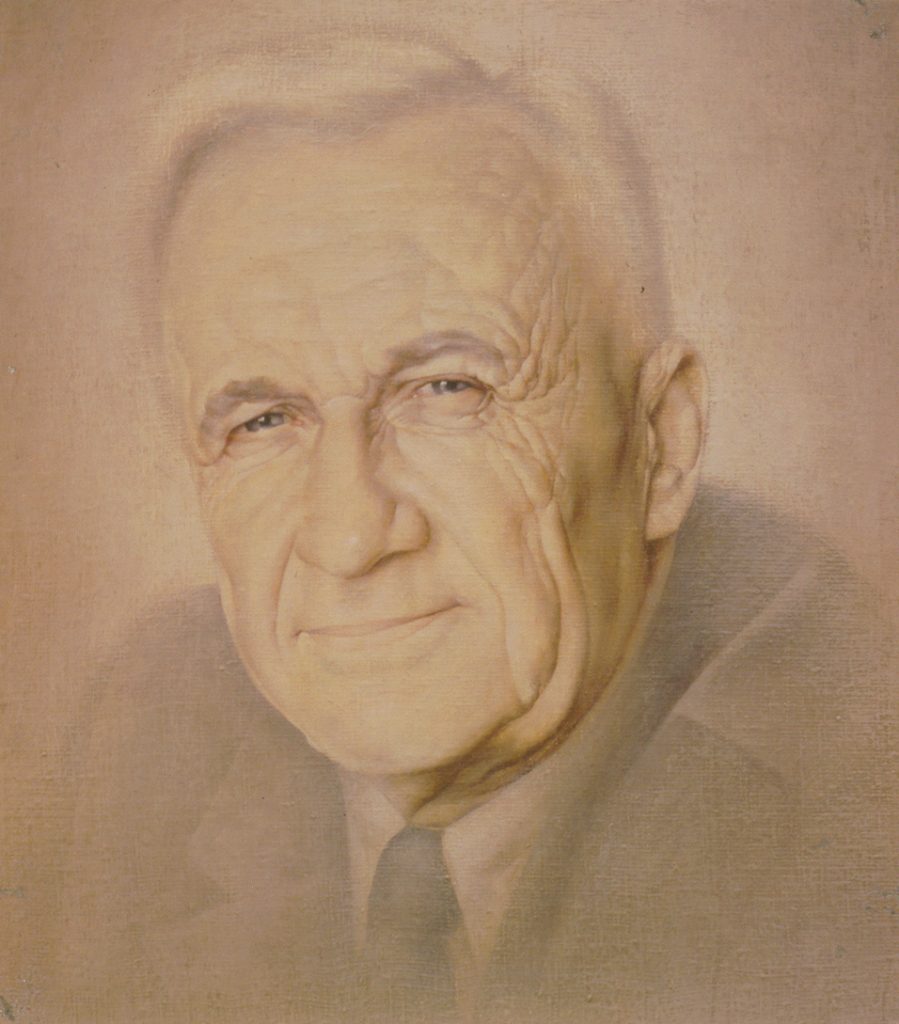

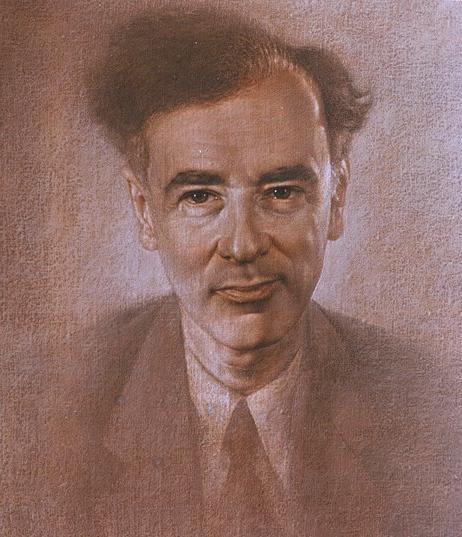

Tamm

All this started with the portrait of Igor Tamm. In 1978 my good friend physicist Leonid Mikheev suggested and arranged an exhibition of my works at the Lebedev’s Physics Institute of Academy of Science of USSR.

Chapiro’s exhibition in Vavilov’s Institute of Physical Problems

Later this exhibition was moved to the Vavilov’s Institute of Physical Problems, which had an old tradition of art exhibitions. In 1981, there was my Solo exhibition in Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy. Due to these exhibitions, I made a lot of friends among physicists.

My works were liked, and someone got an idea to make a portrait of Igor Tamm. Even though he was not alive, the good memory of him was still fresh and around. Tamm was a wonderful human being. Outstanding scientist, he was an exceptionally honest person. Scientists called him “Consciousness of Academy of Science”.

So I began to meet people who worked with him for many years. I started to read memoirs about him. I browsed a lot of his photographs. And finally I watched a movie that physicists jokingly called “One Tamm”, similarly to the phrase that physicists of the past used to describe a unit of consciousness – “One Bohr”, named after the famous Danish scientist, the founder of nuclear physics, Niels Bohr, who was also considered an etalon of consciousness in science.I realized that I am facing a challenging problem, and so I was very nervous. From one side, the person is Academician and Nobel Prize laureate, from the other I wanted to show the simple exceptional human being. I worked like crazy, even with some trembling. I saw the real person in front of me. However, initially he looked somewhat official on the canvas… When the portrait was almost done, I decided to bring it to the Institute for evaluation.

I remember it was winter. Even inside the building nobody took off their coats. All were talking. We were approached by the Department Head, Academician Vitaly Ginzburg (*2003 Nobel laureate in Physics*), with Academician Andrei Sakharov at his side. To me it was a surprise. I knew that Tamm was Sakharov’s teacher and for many years they worked together. As it turned out, physicists asked me to come on this particular day, Tuesday, on purpose, as Tuesdays were the only days when Sakharov was coming to his office at the Institute. It was the period of Sakharov’s persecution by the Government, right before his exile, so he was coming to the office only once a week. We were introduced to each other. I remember his warm and a little bit shy look at me. By that time Tamm’s portrait was installed and Sakharov started to stare at it. Immediately I realized that he liked my work. We talked for 15-20 minutes and Sakharov expressed some suggestions. His manner to talk was so soft, quiet, and even shy, that I was overwhelmed. He asked me to make Tamm a little warmer, something that I already intuitively felt myself. He was indeed too tough and official in my portrait.

Later, when I corrected the portrait, mainly taking into account Sakharov’s remarks, especially improving the lip line, it became warmer. After some time I brought the final version to the Institute and it was unilaterally approved. Thus I made my first portrait of the Nobel laureate.

Sometime later, by request of Evgeny Tamm, the son of the Academician, I painted another portrait of his father, for him. I met Evgeny many times. He, just like his father, became a physicist. In addition, he was an outstanding mountaineer. Those days he was captivated by plans of climbing Everest. I remember his desk was covered by maps and photographs. With great excitement, Evgeny shared with me his plans of this adventure. Strangely, I resisted the temptation to ask him to join his team as an artist, even though it was not realistic at the time, besides that I had no training whatsoever.

Official Reference: (*Here and below, “official reference” means Soviet era Russian encyclopedia*)

Tamm Igor Evgenyevich (1895 – 1971) – theoretical physicist, founder of scientific school, Academician of the Academy of Science of USSR, Government Laureate (1946, 1953), Nobel Prize Laureate (1958), numerous State awards. Worked in the areas of nuclear physics, theory of emission and radiation, solid state physics, physics of elementary particles and controlled thermonuclear fusion.

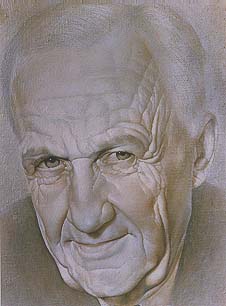

Sakharov

The portrait of Tamm was installed at the Institute’s main conference hall, and physicists asked me to paint a portrait of Andrei Sakharov to his coming birthday May 21. This also was in line with my own intent. I felt great respect towards Sakharov, and I was very saddened to witness all the persecution this remarkable person and scientist was subjected to because of his political views. Unfortunately, I had no chance even to start this work. Sakharov was sent to exile to the city of Gorky. I was able to restart this work only in 1986, after his return from the exile. Sakharov was very busy. He devoted all his time to the struggle for freedom of political prisoners of the regime. He had no time to pose for the portrait. Therefore, I obtained permission to be present at the meetings of Lebedev’s Institute Scientific Board headed by Sakharov. I used to take a seat close enough for me to watch him but far enough to not obstruct the proceedings. I listened, watched, and made sketches. Of course I understood nothing in their discussions. Sakharov was unbelievably modest, even shy. Often he blushed like a teenager, spoke quietly. However, one could feel some stamina in him, some power. The discussions were sometimes very harsh and emotional. When Sakharov was starting to speak everyone would get quiet, respectfully. One could feel great respect towards him. He spoke right to the point. Somehow I got an idea to paint not a standard portrait, but something rather allegoric. To myself I named it “From darkness to light”. I do not know why I got this idea.

Apparently it came from my admiration of him as a human being, scientist, and a fighter. I worked fast, with enthusiasm, and after one month the portrait was ready. I brought it to the same conference hall where my portrait of Tamm was hanging. There were many physicists. All waited for Sakharov. He approached the portrait, stared at it for about five minutes and then quietly, almost mumbling, said: “I like this portrait”. I was delighted. But Sakharov said that he wanted to show it to his wife. I remember we took the portrait, covered it with some fabric and with the whole crowd went outside to Sakharov’s small car where his wife Elena Bonner waited. We were introduced, and then they departed. For several days there was no word from him. I already felt that she did not like the portrait. After three days I called him myself. Sakharov said he is sorry but his wife did not accept the portrait. She did not like my version. She wanted Sakharov’s portrait to be similar to Tamm’s. Of course, I was devastated. My friends tried to comfort me by reminding that Sakharov himself liked it. This portrait later was exhibited at several exhibitions. In particular, I showed it at the famous exhibitions of Leningrad collector Felix Chudnovsky. He possessed the world recognized collection of paintings, mainly from the 20s and 30s. Both Chudnovskys, father and son, were physicists and big sponsors of art. In 1989 Sakharov’s portrait together with several other works of mine were bought by some small gallery in New York. At the very first exhibition the portrait was stolen. Up to this day I have no idea about its whereabouts and what happened to it. But the encounters with Andrei Sakharov I remember always with the great warmth. I am so happy that destiny brought me to know this man. With great pain I watched first Russian post-Soviet assemblies where Sakharov was disrespectfully treated by his opponents. And I am so sorry that he died so young.

Official reference:

Sakharov Andrei Dmitrievich (1921-1989) – physicist and public figure, Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1953. Laureate of Government Awards, State Award of 1953. Works in theory of fundamental particles, theory of thermonuclear fusion, Gas dynamics, Cosmology. *Father of Russian thermonuclear (hydrogen) bomb. Later, adamant opponent and dissident of the communist regime*. Nobel Prize for Peace (1987).

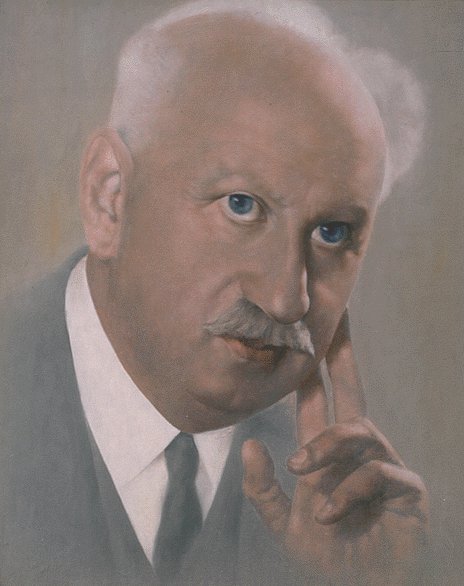

Frank

In the summer of 1978 I was invited to Dubna. This was the kingdom of Academician Ilya Frank. I came there by invitation of his son Alexander, also a physicist. Frank was about to celebrate his 70-th birthday, so Alexander wanted to make a gift for his father. I lived in a good local hotel, and Frank used to visit me there for our sessions. I do not like talking while I work, and he apparently liked my quietness – he was relaxing and thinking his own thoughts. Usually the session longed for a little bit over one hour. There were six or seven sessions like these. Often, after the sessions, Frank used to invite me to his place. We were drinking tea and having long conversations. I remember very well his small cottage and its modest furnishings. At that time I was captivated by Tolstoy’s ideas of simplicity and basic lifestyle. I believed in ideals of goodness and fairness and that sooner or later humanity will come to peace and harmony. I remember once while we were having tea and exchanging philosophical passages Frank smiled and responded to my agitated speech about the future of the human race and the belief that the world will become a better place and all people will become good to each other, with the remark: “Nothing will change, Misha, darling, everything will remain as it was”.

Dubna was a beautiful city of physicists. I used to take long walks at the bank of the river Volga watching its marvelous sunsets. And for the rest of my life I will remember warm, intelligent Frank feeding the furry cats in his garden. Yes, yes, exactly, cats! He adored them, and apparently all homeless cats around adored him too, and were gathering around his feeder. I think there were at least a hundred of them!

By the way, in the hotel where I stayed, I met poet Andrei Voznesensky. It was not our first encounter. I met him earlier, while I was a student. I remember after his concert at the Theater’s Institute at Mokhovaya, I asked him for an autograph. So he wrote after learning that I am an artist: “I am sorry that I quit the art. But You do it! Andrei Voznesensky. Leningrad. 20-th Century.” Once, I forgot something in the hotel and came back (*this was superficially considered as a sign of bad luck*). He said: “Don’t forget to look into the mirror”, (*believed to be removing bad luck*). Since then, when I recall this expression I remember Voznesensky too.

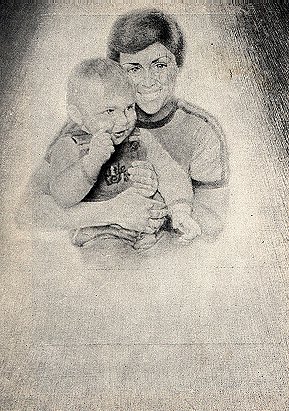

The portrait was finished. Frank liked it but refused to hang it on the wall because he believed it was not appropriate to display a portrait of a live person. Later, at the request of his son Alexander I painted another portrait, this time of Ilya Frank with his son Alexander and his grandson. I called the portrait “Three Franks”. All three looked amazingly alike. I don’t know if the grandson followed the grandfather’s footsteps, he was a very talented teenager then, but his son definitely became a physicist. I was painting in a warm manner, with big pleasure. The portrait remained in the family. However, after the work was finished I felt some emptiness, something escaped from it. I was not as pleased with it as with the first portrait, where Frank was done alone. And so it was my third portrait of a Nobel Laureate….

Official reference:

Frank Ilya Mikhailovich (1908-1990) – physicist, Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1968. Nobel Prize of 1958, shared with Tamm and Cherenkov. Laureate of highest Government rewards (1946, 1954, and 1971). Theoretical and experimental works on physics of neutrons. Created first Soviet fast-neutron nuclear reactor.

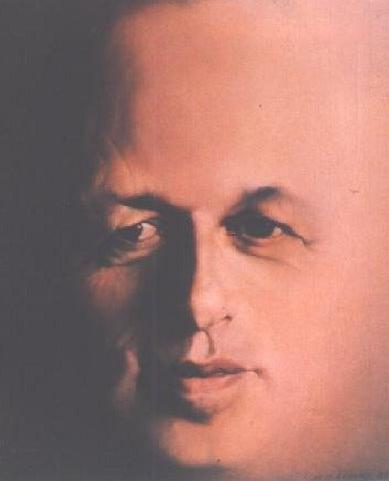

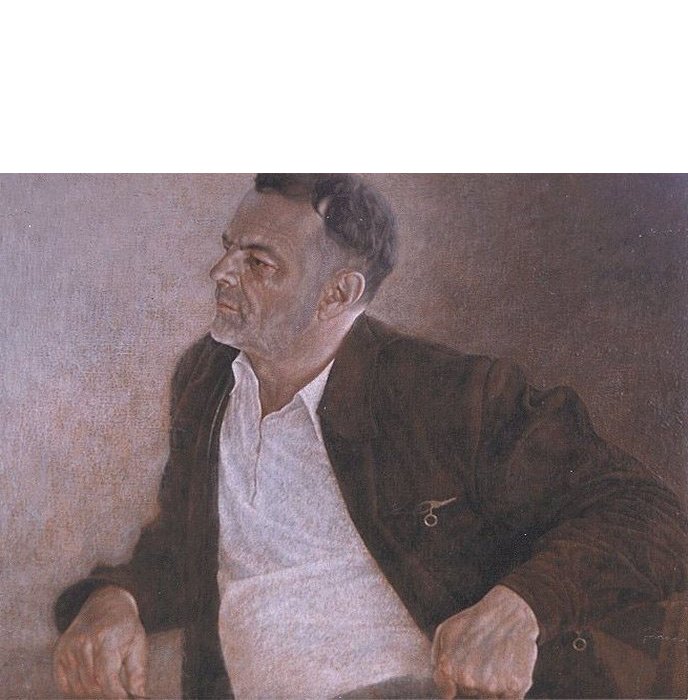

Leontovich, Landau, Lifshitz, Artsimovich

In 1980, by request of physicists of the Kurchatov’s Institute for Atomic Energy, I started to work on a portrait of Academician Mikhail Leontovich. Our first encounter, as I now remember, happened in the Institute’s corridor. I stood there with his son Alex. Suddenly, from the other end, a group of people had emerged among whom one was obviously different, significantly taller, thinner and stronger. He walked resolutely, so one could feel he was preoccupied by his own thoughts.

He reminded me of Don Quixote. When the group reached us Alexander slightly stutteringly said: “Dad, this is an artist who wants to paint your portrait”. For a moment Leontovich the senior stared down at me and then said: “So what?”, and proceeded on his way. Later of course I realized that Leontovich did not mean to insult me at all. He was so preoccupied by his thoughts that the rest of the world did not exist to him at that moment. Rapidly walking, strangely gesturing, with tangled hair he moved around the Institute with tremendous speed. Besides heading the Institute he also served as a Head of the publishing Board of a physics journal that was headquartered at the Vavilov’s Institute. His day was scheduled literally by minutes. Several times I had an opportunity to watch him at the proceedings. He had a very unique way of talking, amazing elasticity of his hands… and also, he always had a cigarette in his hand. And so, like this, somewhat removed, embedded in his thoughts, with cigarette in hand, I painted him. I could not guess that Leontovich had very little time left. I exhibited the portrait at Malaya Gruzinskaya where avant-garde artists exhibited their works, but right before the exhibition Leontovich died. I remember as Alex came there. He was walking back and forth, approaching his father’s portrait and then walking away from it, and I saw tears in his eyes. To my big surprise the portrait which was done in a strictly realistic manner was well taken by artists of all directions. I was also pleased to learn that it was liked by the great poet Evgeny Evtushenko. One day I left the exhibition for a few hours. When I returned back I was told that Evtushenko was there, wanted to talk to me, and has been waiting for me. He has left a very warm feedback in the visitors’ journal. I don’t remember its exact wording now but I do remember that Leontovich reminded him of Andersen’s characters. It is this portrait near which I met the Shteinberg couple, Godda and Evgeny. Huge fans of Maya Plisetskaya, they approached me with the words: “Here we found an artist for Maya”. But more about that later. The Leontovich portrait was installed in the Institute’s library. And only now I realized that I never asked Alex if his father ever saw the portrait before his death, or whether he liked it.

I remember though that first people who saw the portrait were the Lifshitz couple.

They were very delighted by it, said so many flattering words – like opening a green light to me. Academician Evgeny Lifshitz lived in a building on the Institute’s campus, where many other famous physicists lived for many years.Lifshitz and his wife Zinaida welcomed me, so I visited them very often. They were telling me about scientists, recalling those with whom they worked, who was at the foundations of Nuclear Physics. By their request I painted a portrait of Lev Landau with whom Lifshitz worked for many years. I painted him by photographs and memoirs of Lifshitz, his best friend and a colleague. Landau was great physicist. His series of books on Theoretical Physics became textbooks for physicists of several generations. He was laureate of many prestigious awards including Nobel Prize of 1962. Thus, I acquired a fourth Nobel laureate on my resume. Unfortunately, Lifshitz died soon, and his wife has asked me to paint his portrait too. Both portraits, Landau and Lifshitz, are now in Moscow and belong to the Lifshitz family.

About the same time, by request of a widow of Academician Lev Artsimovich, I made his portrait, also by photographs and memoirs of his colleagues. This portrait was hanged right by the portrait of Leontovich. So, they are sort of looking at each other.

Official references:

Leontovich Mikhail Aleksandrovich (1903-1981) – theoretical physicist, founder of scientific school of radio physics and physics of plasma, Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1946. Works on statistical physics, radio waves propagation, antennas theory. Since 1951, Head of theoretical research on plasma physics and controlled thermonuclear fusion. Lenin Prize of 1958.

Landau Lev Davidovich (1908-1968) – theoretical physicist, founder of scientific school, Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1946, Laureate of Government rewards. Works on magnetism, super fluidity, solid state physics, nuclear physics, and quantum electrodynamics. Lenin Prize of 1962, Government award (1946, 1949, 1953). Nobel Prize (1962). Author (in co-authorship with Lifshitz) of classical course of Theoretical Physics (1962).

Lifshitz Evgeny Mikhailovich (1915-1985) – theoretical physicist, Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1979. Works on ferromagnetism, molecular interactions, and relativistic cosmology. Lenin Prize (1962), State Prize (1954). Author (in co-authorship with Landau) of classical course of Theoretical Physics (1962).

Artsimovich Lev Andreevich (1909-1973) – physicist, Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1969. Works on atomic and nuclear physics. Head of research in physics of high-temperature plasma. Under his supervision the first thermonuclear reaction was realized.

Prokhorov

In 1985, I painted a portrait of one more Nobel Prize laureate in Physics – Alexander Prokhorov, for his 70th birthday, by request of his coworkers at Lebedev’s Physics Institute. Director of the Institute at that time was Nikolai Basov. Bright scientist, generator of ideas, Prokhorov was often arguing with Basov and as I was told he was not in good relations with the Director. Institute’s employees even called them jokingly “Basov and Contra-Basov” (*second meaning: bass and contrabass*). Nevertheless, despite the fighting, they made together remarkable discoveries in science, so that the Nobel Prize was deservedly given to both of them. They worked in the area of quantum electronics and were first in the world to create a quantum generator – a maser. Alexander Prokhorov was a very likable person. Everyone in the Institute liked him. Doors to his office were always open to everybody. He never kept distance and was very democratic. One could never guess that he was an Academician. He had a very remarkable appearance: tall, long-faced, with a somewhat pointy nose. Most of all I was amazed by his eyes. They were always shining, sparkling with merriness. He always joked and had a great sense of humor. I remember his 70th birthday party to which I was kindly invited. The tone was certainly defined by the hero of the day himself. I was charmed by the whole atmosphere of the party. There was so much laughter, merriness, and jokes. Once again, I realized that physicists are not nerds at all, and they were quite deservingly called physicists-lyricists by some. The Prokhorov portrait was ceremonially presented to him at this party, and now belongs to the family of the Academician. Unfortunately, I don’t have a photograph of it.

Official reference:

Prokhorov Alexander Mikhailovich (1916-2002*) – one of the founders of quantum electronics. Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1966, Laureate of Government Prize (1969). Works on lasers and masers, non-linear optics. Lenin Prize (1959), State Prize (1980), Nobel Prize (1964).

Kantorovich

In 1987, I started to work on the portrait of the Laureate of the Nobel Prize in economics Leonid Kantorovich, by request of his son Vitaly Kantorovich. I was introduced to Kantorovich not long before he died. He was very sick and was coming home from the hospital for short breaks. I met him several times. Our conversations were short because he was quickly getting tired. His stories were extremely interesting. I saw that he realized that his days were counted, but had not shown any fear to his family. On the other side, his friends and relatives also, to the best of their ability, tried to brighten his last days. Once, I came to his place. There were several of his closest friends present. A dinner was served. Unfortunately, Kantorovich could not eat most of the food because of the doctors’ prohibition. From our conversations and from his colleagues, I understood that his way in science was very interesting. A bright mathematician, he was very much interested in the country’s political life. Endless reports and “decisions” of plenums and assemblies of the Communist Party puzzled and irritated him, especially as a mathematician, by their uncertainty and empty and vague formulations. It prompted him once to write a private letter to Khrushchev with suggestions on scientific analysis and solutions to economic problems of the country. Kantorovich started to work on mathematical methods of solving those problems. Thus, he created new science – mathematical economics. His contribution was tremendous. In 1975 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics, thus becoming the first mathematician laureate of the Nobel Prize. The common belief is that a mathematician is never awarded the Nobel Prize because of the will of Nobel who was in a conflict with leading Swedish mathematician Mittag-Leffler. Kantorovich died before I finished his portrait, so he had no chance to see it. I remember that during the funeral there was fine drizzling rain. The cemetery was full of people, the whole scientific elite was there. There were speeches, warm words of the last goodbye, and I saw that everybody was sincerely sad about his death. Several minutes I stood near the grave too. This portrait I did for his family. But after some time, scientists of Novosibirsk Academ-Gorodok (*scientific center of Siberia*) where Kantorovich worked in the past asked me for one more portrait of him. I painted a second portrait, a little bit differently from the first one, and sent it to them.

Official reference:

Kantorovich Leonid Vitalievich (1912 – 1987) – mathematician, Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1964. Main works are on functional analysis, computational mathematics. Founder of linear programming. One of the founders of theory of optimization in planning and management. Lenin Prize (1965), Government Prize (1949), Nobel Prize in economics (1975).

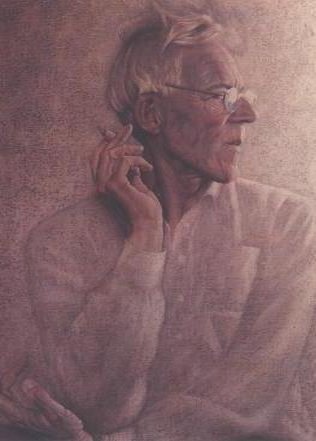

Ioffe

The last among portraits of famous physicists that I was fortunate to make was a portrait of Academician Abram Ioffe.

The work was requested by physicists towards celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Leningrad Physical-Technical Institute (famously, Phys-Tech) which was named after Ioffe. He was fondly called “Papa Ioffe” because he was considered a father of Soviet Physics. The portrait had to be done by photographs, very quickly, in order to be finished by the deadline, the anniversary. I specially traveled to Leningrad from Moscow with the finished portrait to the official meeting of physicists in Phys-Tech. I remember I was warmly welcomed by the Institute’s Director Zhores Alferov who this year (*2000*) I learned also was awarded Nobel Prize. Back then he was very funny, always joked. He even told me a couple of anecdotes using forbidden words. After that, we proceeded to the conference hall where my portrait was warmly accepted. But, to be honest, there was also an opinion that Ioffe’s eyes went way too blue. Up to this day the portrait is hanging on the Institute’s wall. Interestingly, a month ago, I watched a program on Russian TV. One of the stories was about Zhores Alferov. Imagine, they show his office and on its wall there is the portrait of Ioffe done by me. It felt so good.

Official reference:

Ioffe Abram Fedorovich (1880-1960) – physicist, founder of Soviet School of Physics, Academician of Russian (and later USSR), Academy of science since 1920. Laureate of Government Prize (1955). Pioneering research in semiconductors. Works on elasticity, resistance, electro-conductivity of solid state. Lenin Prize (1961), Government Prize (1942). Founder and first Director of Physical-Technical Institute, and Institute of Semiconductors.

Kikoin

In that period there was another delightful encounter that unfortunately did not end in a portrait. Destiny brought me to Isaac Kikoin. Once, I traveled to his countryside cabin. At that time he with his brother, also a physicist, was working on a physics textbook for students. They were working intensely. Nevertheless he had found time for me and we had a conversation that lasted for two and a half hours. I remember that I was so overwhelmed by what I heard that I came home and wrote down everything he told me. His life was unbelievably interesting. He became a Doctor of Science when he was very young, 26 or 28, I don’t remember exactly. In 30s he worked with Niels Bohr. When he worked in Germany he had witnessed the start of the Nazi’s uprising. He had listened to speeches of Hitler at the cities’ squares. For many years Kikoin’s name was kept a secret, he was surrounded by guards. The first time I saw Kikoin was at the traditional celebration “Meet the Spring” which was organized annually at the Kurchatov’s Institute. That day of 1981 the celebration coincided with my first solo exhibition. There was everything: parade, dances, songs, games. Physicists celebrated fully. Already at a respectable age, he was nevertheless very active and funny. I remember he had to cut the tape at some sculpture covered with white sheets, standing at a quite high base. Kikoin had to reach very high. When the sheets fell down there was a nude female figure, apparently it was “Miss Spring”. I was very impressed by this extraordinary person, by his life full of interesting events, and I was dying to make his portrait. But for some reason it did not happen…

Official reference:

Kikoin Isaac Konstantinovich (1908 – 1984*) – physicist, Academician of Academy of Science of USSR since 1953, Government Prize (1951). Works on atomic and nuclear physics, engineering and solid state physics. Lenin Prize (1959) and six State Prizes. (*Kikoin was one of the creators of Soviet nuclear bomb.*)

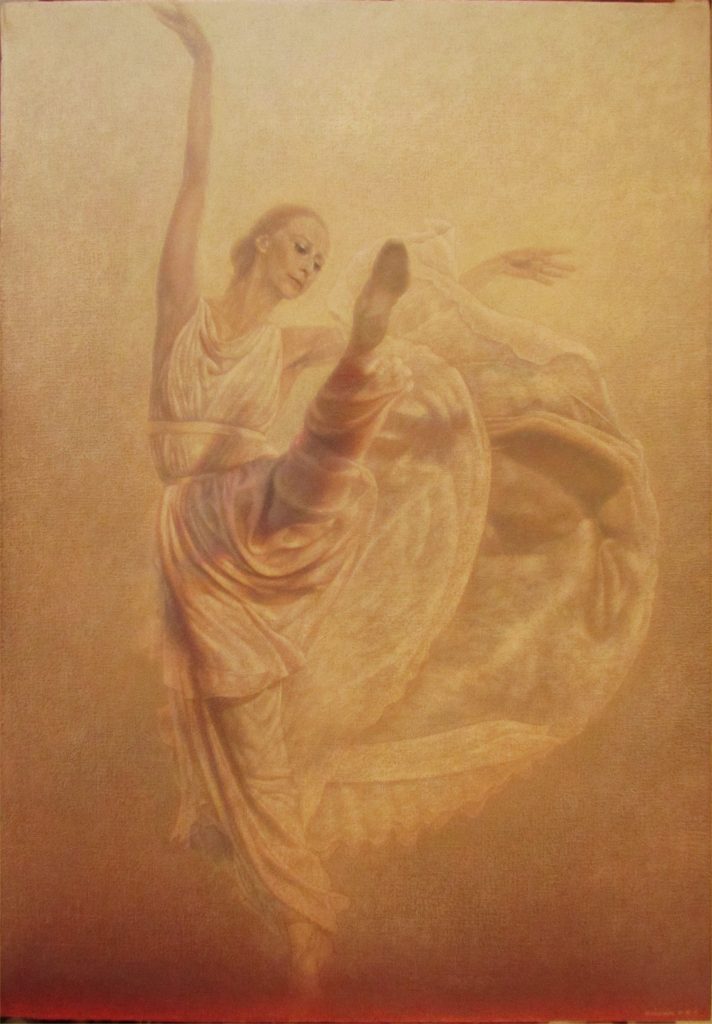

Plisetskaya

Portrait of Maya Plisetskaya. Perhaps this is the most memorable event of all. At the Fall exhibition at Malaya Gruzinskaya in 1980 I was approached by the spouses Shteinberg who were great lovers of Maya Plisetskaya, as we would say today – fans. They would not miss any performance where she was involved. Once, they took me with them to one of the performances, and thereafter took me to the back door where Plisetskaya fans were always crowding. They introduced me to Plisetskaya, and told her I am an artist. However she could not possibly pose for the portrait. Her time was scheduled by minutes. I got an idea to paint her dancing Isadora in a famous choreography by Maurice Bejart about the great French ballerina Isadora Duncan. Up to this day, I cannot believe how I was able to complete this task.

The portrait, as everybody claims, went out very dynamic and light. Maya is almost flying in it. Apparently, what had helped is that I watched a lot of performances with her, and the turbulence of her mind-boggling twister dance swept me too. When the portrait was ready, I called Plisetskaya. Maya promised to stop by for about 10 minutes. She stayed for one and half hours! I remember as she stormed into my studio. Elegant, beautiful, with a wonderful light face, with a sparkling shining look… I was so nervous. Will she like the portrait? And thus, here is Maya Plisetskaya in front of her portrait. I even lost my breath. Famous Maya Plisetskaya in my studio, in my home! From the very first sight she liked the portrait, which to me was the most important of all.

After that, she started noticing some little details, making some remarks, expressing some doubts. One finger did not fit into the picture. I have been trying to find a satisfactory explanation for this, and finally said: “Maya Mikhailovna, any canvas is too small for you!” The farther, the more: the breasts are not so good, and the armpits not so great… By the way she was 55 then. And then she agreed with everything. Most of all she liked the sense of weightlessness and plasticity. She liked the thrilling red strip in the bottom of the picture. “What’s this red strip for?” was her last question. I said that by this allegory I tried to project that all her life she walks by the edge. She sighed and sat down to my ugly sofa that was so old and broken, with strings coming outside, that I covered it with a carpet. She began talking about problems in the Bolshoi Theater that were bothering her. She was very sincere with me. I could feel she had a lot of pain. Many people were named that day in the way they do not want to hear. At one point I interrupted her because I thought she was not comfortable on my sofa: “Maya Mikhailovna! Perhaps you are not comfortable there?” She obviously did not like to be interrupted and said: “I would be comfortable, if I would not be interrupted”, and continued her story. Thus, in the conversation, one and a half hours flew by. Plisetskaya immediately came up with an idea that this portrait must be bought by the Bolshoi Theater. She really liked the portrait but the dimensions were too big to fit in her home. A few days later, by recommendation of Maya Plisetskaya, the Director of the Museum of the Bolshoi Theater stopped by. He liked the portrait too, and promised to do everything he could in order to arrange the purchase. However Plisetskaya had a lot of enemies. First of all it was the Minister of Culture and the former Director of Bolshoi. Besides that, I was an unknown artist. It was so easy to deny the deal. Despite all of Maya’s efforts she got nowhere. Once, she called me asking for the portrait’s exact dimensions. Together with Rodion Shchedrin, they were building a new house on the Baltic Sea, and apparently were considering an idea to put it there. But it would not fit there either.

In 1986, I think in the spring, at the Bahrushin Museum in Moscow there was an exhibition devoted to Plisetskaya’s anniversary. I was asked to provide my portrait to this exhibition. Of course I happily agreed, and when I came to the opening I saw my portrait in the very center of the exposition, which was very flattering. It was a very unusual exhibition. There were photographs from her performances and costumes. There were works of other artists too. There was a wonderful watercolor portrait done by artist Fonvizin. At the opening there were many friends of Maya, there were many warm words about her. My portrait was warmly taken by all. The Director of the Museum wanted to buy it. And again, unfortunately, there was Maya’s enemy at the purchasing board, who objected and broke the deal. After some time, the exhibition was moved to Leningrad. It was displayed in the Summer Garden, at Rossi’s Teahouse. I traveled to the opening too. And to my great joy the painting was purchased by the Leningrad Theater Museum. I was happy, it was the only work of mine bought by the Government. By the way it was not the only portrait of Plisetskaya that I made. For her 60th birthday a group of her fans placed an order for another portrait of her. This time it was a small sized portrait. I featured Maya waist up, in a red home dress, with loose hair down. I was working quickly, since I had to make it by her birthday. And thus, at the Bolshoi Theater, November 20th, 1985, with a crowd of her fans and all tickets sold out, I brought the portrait to the Theater.Vladimir Shahmeister immediately took it from me and raised it above his head. Like a magnet, all were looking at him. By the way, Vladimir was an illustrator for Plisetskaya’s book called “I am Maya Plisetskaya”. The fans wanted to present the portrait to her right at the stage, but there were so many officials with speeches, and the program was so tight that the only opportunity to present it came behind the stage. I was happy that some part of me remained with Plisetskaya. I became her true fan too. Unfortunately, then, in all the hurry, I did not even make a photograph of this portrait.

Year 1996. I already lived in Canada. Once, I heard that Maya Plisetskaya was coming to the International Festival of Ballet that annually takes place in Montreal. We met literally for 15 minutes. I came to the service door. Maya was glad to see me, it was a surprise to her. Yes, we both changed. She was already 70. And yet, that evening she danced “Swan Lake”!

Shostakovich

I always liked the music of Shostakovich. Once, working in my studio, I heard on the radio a quartet of Shostakovich. Suddenly I felt I wanted to paint his portrait. I got a vision of horizontal composition in front of my eyes. A profile image that appears from darkness and dilutes into light. For several days I was enchanted by the picture born in my imagination. I was introduced to the widow of the composer, Irina, and I became a frequent guest at Nezhdanova Street, in the famous House of Composers. I was welcomed there. I was shown a lot of photographs, and even one rare documentary movie about Shostakovich that contained many unique scenes.

And thus, when the portrait was almost ready, Irina came over with a famous movie maker Tengiz Abuladze, apparently they were friends, to my place at Novosloboskaya. They liked the portrait but for a reason unknown to me she did not decide to buy it. Instead, she expressed desire to arrange its purchase by the Union of Composers.

Eventually, she talked to a secretary of (*famous composer*) Tihon Khrennikov who then was the Chair of the Union. She said that one young artist made a brilliant portrait of Dmitry Shostakovich. But then there began a non-pretty story that left me bitter and frustrated. There was the celebration of the 75thbirthday of (*famous composer*) Dmitry Kabalevsky. Khrennikov agreed that to the celebration which was taking place in the House of Composers I could bring my portrait, so that everyone could see it. So, there is jubilation going on. I am sitting outside, in the hall, apparently for more than an hour, waiting to be called. The portrait is here, already in the frame. I was very excited. And finally I am called. I entered the room bearing the portrait, and I remember the unilateral reaction of approval by everyone in the room. By the way, it was the whole musical elite there. Many knew Shostakovich personally. They began to congratulate me. All were shaking my hand. It was a pleasure to hear warm words from Jan Frenkel, Alexandra Pakhmutova, Evgeny Svetlanov, and many other famous composers, singers and musicians. I was also approached with warm words of congratulation by the hero of the day composer Dmitry Kabalevsky. Khrennikov also liked the portrait, and immediately introduced me to the Head of the Music Fund of USSR who gave me his phone number and said he would call me himself. And then… I realized there were background checks. Who is the artist? From Malaya Gruzinskaya (*i.e. related to the avant-garde movement, not approved by Communists*), which is almost like a crime. Not long ago there were fights of artists against the regime. The avant-garde exhibition in Bitsevsky Park was brutally wiped out by bulldozers. Malaya Gruzinskaya was the only place where artists unwelcomed by the communist elite were allowed to exhibit their works… In short, the portrait was liked, but not so was the author, an unknown artist, not a member of the Union. Nevertheless, after some time I was called by the secretary of Composers’ Union who told me to expect guests. My wife and I went into panic mode, started to make order in our home and other preparations. And here it is, the doorbell rings. It was Khrennikov himself and with him – he introduced me – Ponomarev, the first Secretary of the Union of Artists. They came right from the opening of the memorial of Yuri Gagarin. They stayed for about 20 minutes at my place. The portrait, I think, was liked by Ponomarev, but the doubts about my resume remained. I already realized that there is no chance for the purchase, but Ponomarev said nevertheless he would send his deputy to me. Indeed, after a week, there came his deputy, Academician, and graphics artist. And again I was told that the portrait is good but there is need to think more. After that, there was long silence, and the portrait stayed with me. I felt frustrated. Once, I called the son of the composer Maxim, with whom I spoke over the telephone several times before. But he was already preoccupied by his upcoming emigration from the USSR. Once, the daughter of the composer, Galina, came but she had no means to buy the portrait. Eventually, it was purchased by the same gallery in New York that purchased Sakharov’s portrait, and its further fate is unknown to me.

Rodnina

In 1980 there were the 20th Summer Olympic Games in Moscow. The city quickly improved to be unrecognizable. There were many new pretty buildings built for the Olympics. I remember the grand opening – a marvelous, spectacular event. Everybody marked this event to the best of their abilities. Artists were not an exception. At Malaya Gruzinskaya, for the Olympics, there was an exhibition devoted to sport. I exhibited a portrait that was named “Olympic Madonna”.

That year the Winter Olympic Games were held in the US, at Lake Placid, NY. There, our remarkable figure ice-skater Irina Rodnina became triple Olympic champion. It was her last Olympics, and the whole world remembers her wonderful eyes full of tears when she was awarded the medals. I spent hours by the TV watching Irina. The work on the portrait however started earlier. I had a friend, Alex Ivanitsky, who was three time Olympic champion in classical wrestling. At that time Alex was the Chairman of the Soviet Sport Committee. Once, he visited me at my home, in my studio. He liked my paintings and we became friends. Towards the Olympic Games I decided to paint someone among famous sportsmen. Eventually, I picked Irina Rodnina. At the time she was apparently the most famous and commonly loved among all. I asked Alex Ivanitsky to introduce me to her and to communicate my desire to make her portrait. Thus Irina invited me to her training session. I remember my first impression. When she approached me in the hall of the sport complex she looked so tiny. However, when she shook my hand I felt her strength. Soon we were joined by Alex Zaytsev (*husband and partner*), also of average height. On the TV screen when they were rapidly moving along blue ice they looked huge to me, especially Alex. Irina and Alex invited me to watch them at the arena. By this session alone I realized how much energy they were spending. They were training very intensively.

Those were the last days before the Olympics. Their trainer then was Tatiana Tarasova. I remember all the scenes. Of course, in their duet, Irina was the leader. She often raised her voice, was angered, when something was not coming out right. One day I went to their home in order to make a series of photos. There, I saw their son – little Alex. I immediately had an idea to paint Irina with her son. In general, these theme, mother and child, motherhood, thrills me. I have done many paintings on this subject. The portrait went out very warm and kind. In the time when I was working on it they were working hard too at the Olympics in America. Upon their return they have come to me to see the portrait. Irina was already a triple Olympic champion, and Alex was a double champion. They liked the portrait very much and were going to take it right away, but I asked them to leave it for a while to me, so that I could exhibit it at Malaya Gruzinskaya.

Yakushev

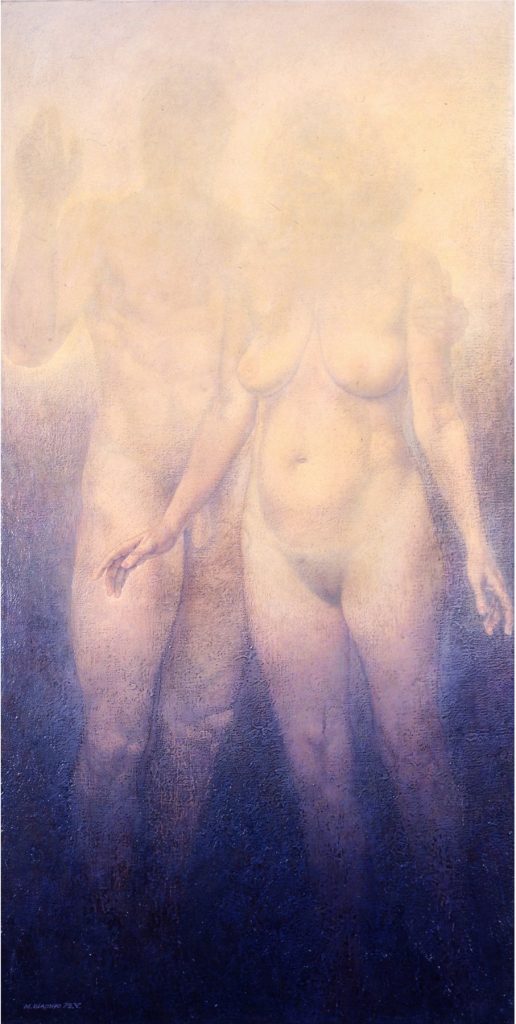

And one more Olympic champion posed for me for my paintings. It was Alexander Yakushev. He was a celebrated sportsman, ice hockey player of the Moscow team “Spartak”. There was a famous triplet: Zimin-Shadrin-Yakushev. For many years this triplet was an integral part of the Soviet Olympic team. During the matches in Canada in 1972 this player made great impression, even more than perhaps Kharlamov and Maltsev. Besides master technique, Alex had a very solid physical appearance. Experienced Canadian defenders had hard times handling him. For Canadians he was a real hockey player – big, strong, muscular and tough. Besides, he was a very attractive man. And certainly his titles were very impressing – multiple world champion, Olympic champion, etc. And so, I thought about a picture which I called for myself “From darkness to light”. This theme is very dear to me. I tried to explore it in the Shostakovich portrait, in Sakharov’s one, and in others. And here I thought of a composition of two naked figures – male and female. They are coming from darkness and moving towards light gradually diluting in it. By my design they are supposed to be not very young people, people who already have lived through some experience, having known the life. Eventually the picture was named “… and eternally”.

I decided to realize this composition on a big vertical canvas. But I needed the models. The female model was found pretty quickly. But the male model was a problem. And here, once again, I got help from Alex Ivanitsky. He took me to the hockey game where one could find such a warrior. He immediately pointed at Alexander Yakushev. I started to watch Alex at the game, and I liked him a lot. However, I doubted that such a famous sport star could agree to pose for me. Ivanitsky introduced us to each other and asked Alex to help me. And to my big surprise Alex agreed right away. He turned out to be very simple, not at all a snobbish, guy. He came to my place about five times. He posed almost naked. He had a very pretty enlightened face, and needless to say a very impressive body. Once there was a little mishap. Alex was standing on two little coffee tables which turned out to be too weak for his big body. At one moment the tables leaned to each other… and Alex fell to the floor. His great reaction saved him. I remember he said: “Wouldn’t it be funny to get an injury not at the hockey field but in the artist’s studio?”

I was confused, I felt guilty. Fortunately, everything went well. Thereafter, Alex invited me to several hockey games. Unfortunately, I was not good as a hockey fan. One more interesting detail: the last name of the woman who posed for the painting was Yakushevskaya (*variation of “Yakushev”*). There are some interesting coincidences in life…

These simple, unpretentious stories by Mikhail Chapiro gave me a lot of pleasure. Listening to his memories, I almost lived with him those moments of his life, of his work. I felt like I met myself all those famous people whom he met and painted in his portraits. It is sad, however, that the fate of some portraits like Sakharov’s is unknown and that in the artist’s archive some photographs of his works are missing…

Big thanks to you, Master.

Wish you further success!

Irina Lapina

*Year 2000*